Agile antipatterns are organizational impediments to agile practice which ought to be challenged and removed. They are best tackled by means of the patterns which are most likely to eliminate them.

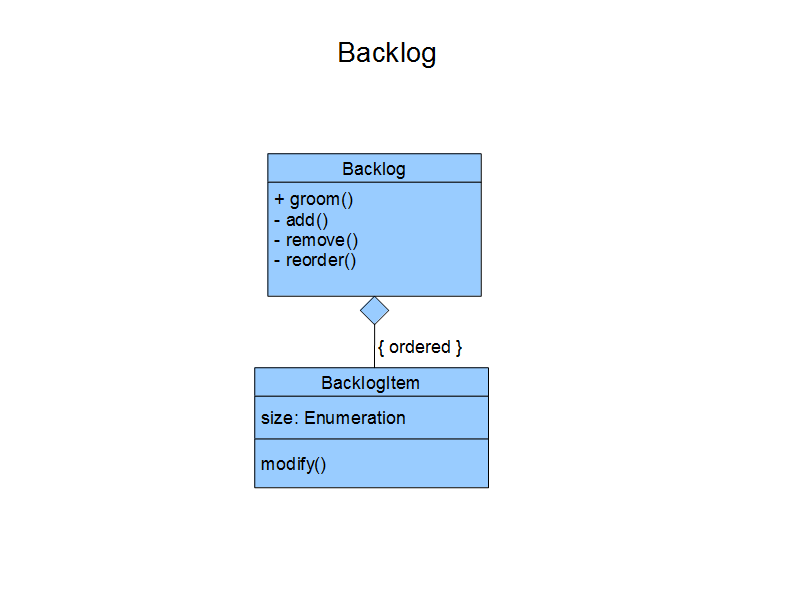

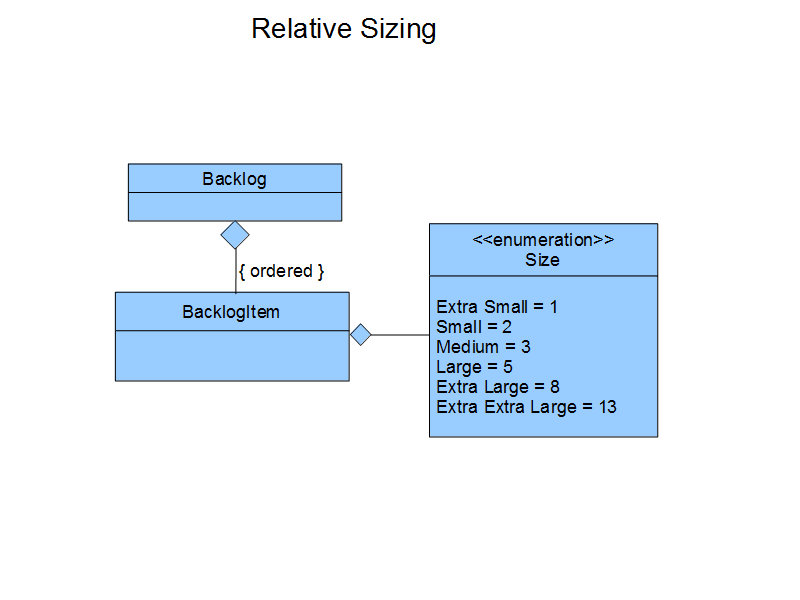

Cherry Picking: Team members are often tempted to select those items from a backlog which they expect to be the most gratifying for them, or the easiest to do. Swarming on items may help, as it requires team members to collaborate more closely.

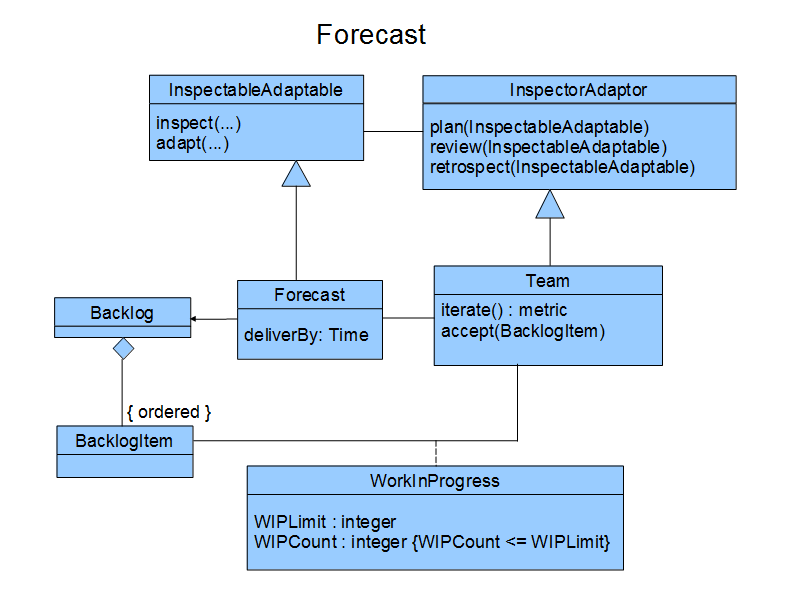

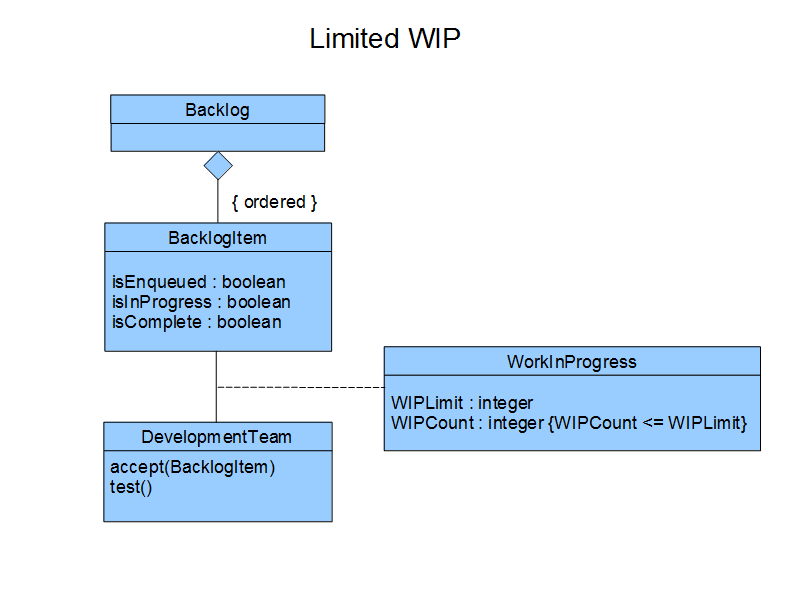

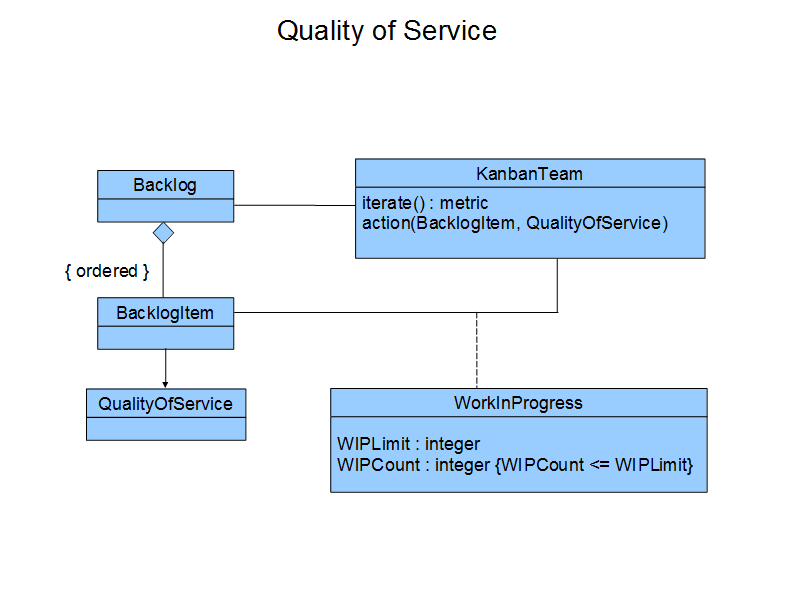

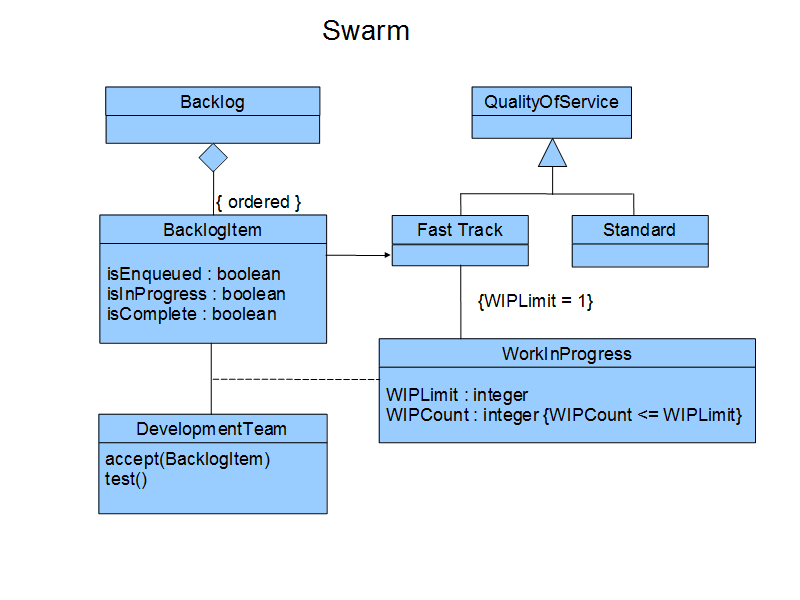

Cloned Avatar: If development team members are given unclear priorities in a high-pressure environment, they can be tempted to start development on an item without first completing the work they have in progress. By duplicating their avatar, they can then claim to those exerting the pressure that work is underway. Limiting Work in Progress is likely to be beneficial as a pull-based system ought to be encouraged.

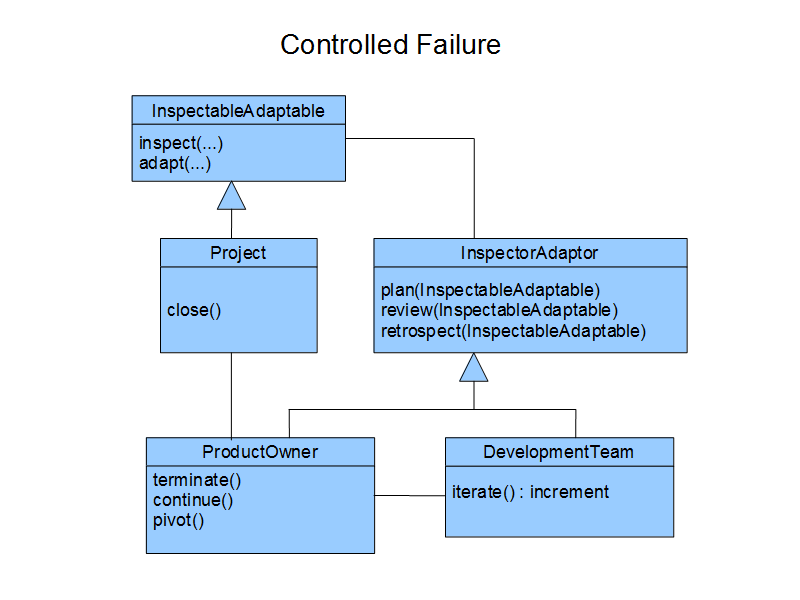

Death March: It can be politically difficult to cancel a struggling initiative if it has already absorbed significant resource. To do so may imply that the project has been a poor investment and that the time and money committed has been lost. Stakeholders would prefer to continue with a failing project and hope for sudden and improbable change. Controlled Failure must be recognized as an option.

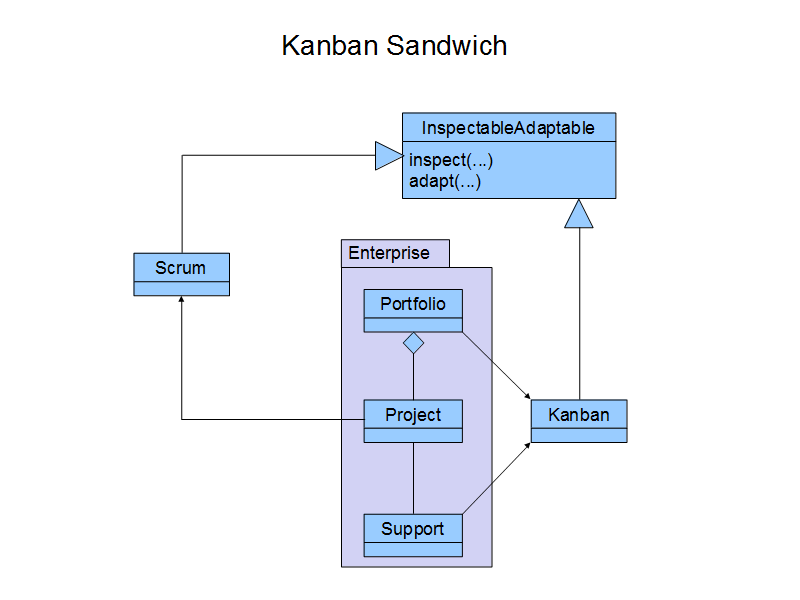

Disguised Project: Some changes to IT systems can be trivial in nature, such as minor amendments to site content or defect fixes. This type of work is considered to be “Business As Usual” (BAU) and as such it is often absorbed by the organization-at-large as an operational expense. Departmental stakeholders who want more substantial changes must usually resource a suitable project from their capital budgets. They therefore have an incentive to disguise such work, either by misrepresenting it as a normal operational small change, or by breaking it up into a series of small changes that they hope will slip through a BAU work-stream unnoticed. The Kanban Sandwich and Value Stream patterns might provide remedy.

Distributed Team: Physical constraints, such as desk space and the wider geography of an organization, may inhibit the co-location of team members. The need for agile team members to work in proximity to each other can present logistical issues that managers are unwilling to overcome. As such, a logical team boundary will be made to span physical boundaries. Managers can thus avoid an immediate resourcing issue, while offloading the management of any risk incurred to the teams themselves. Co-location is generally advantageous and can reinforce the Teamwork pattern.

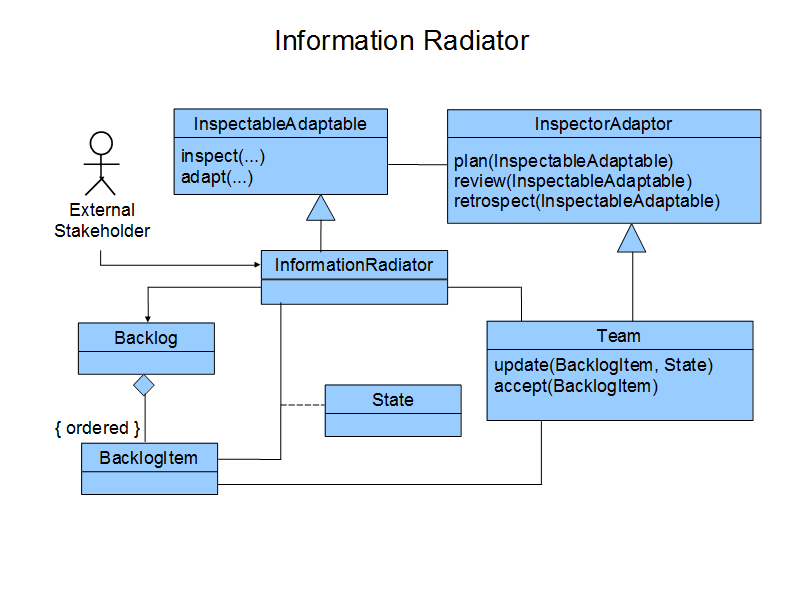

Management by Reporting: Highlight issues and concerns, while deferring the risk of taking action to others…or at least to a later date. The hope is to avoid personal exposure should there be negative consequences from taking action. Management by Exception can be a more practical alternative in so far as it establishes clear tolerances.

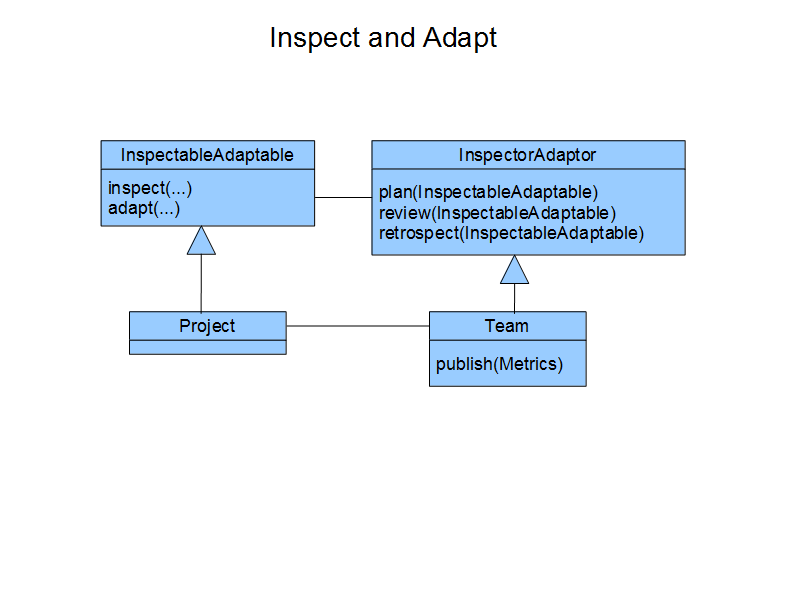

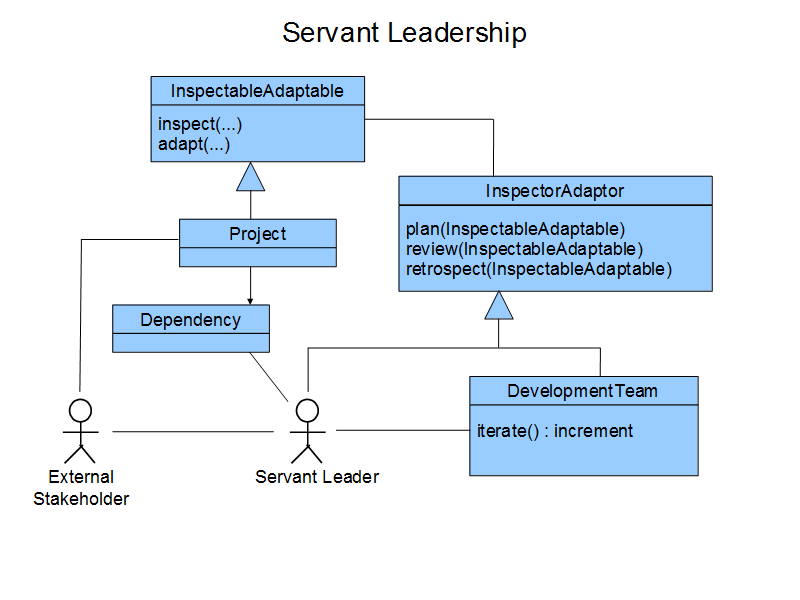

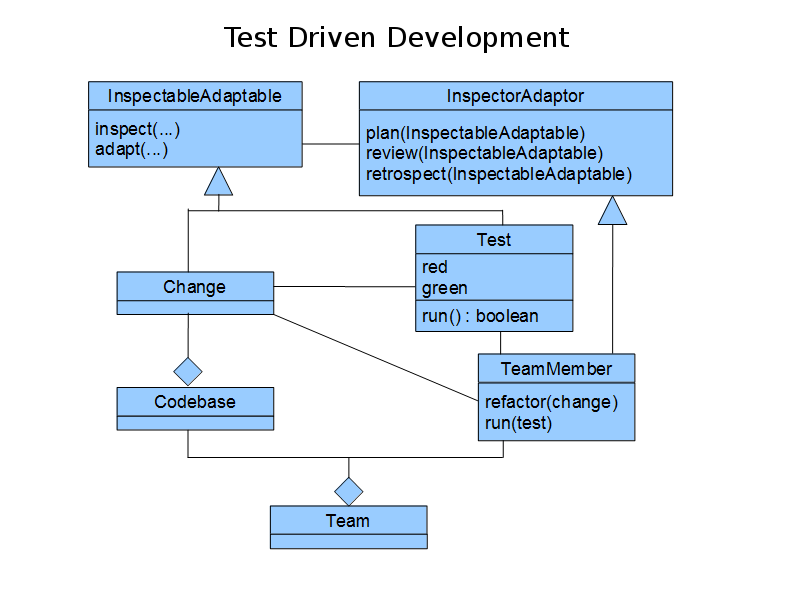

Micromanagement: Managers can find it hard to delegate operational responsibilities. There are a number of possible motives for a manager wishing to retain control. For example, the manager may not trust others to perform the duties satisfactorily, or he or she may simply enjoy dealing with operational matters. A servant leader will coach more constructive behaviors, and the team should be encouraged to inspect-and-adapt its own way of working. Again, establishing clear tolerances through Management by Exception can help.

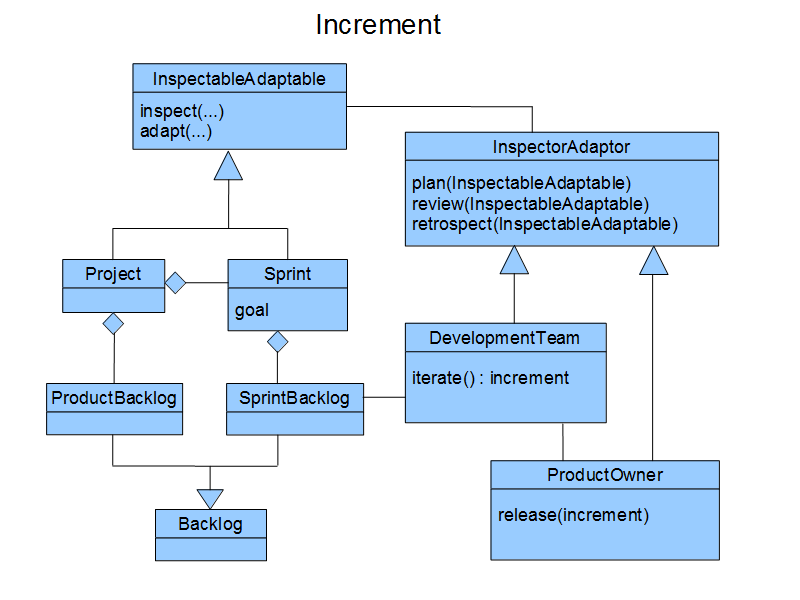

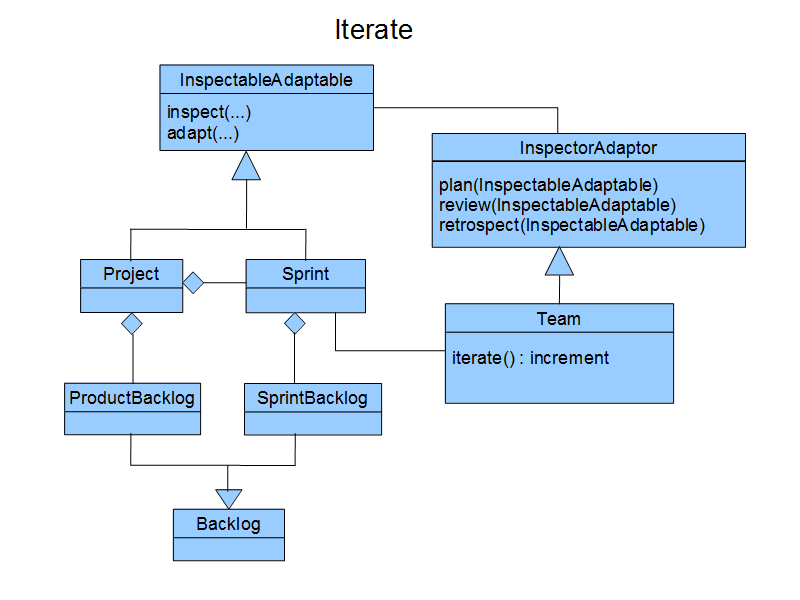

Sprint Zero: Set up an agile project, while contextualizing unplanned initialization overheads in agile terms. No value is released and empirical process control is not established. Ensuring that the Iteration and Increment patterns are used together can be wise.

Time Theft: Agile teams draw their work from prioritized backlogs, which means that those waiting at the bottom of the queue may expect some degree of delay. Such parties may thus be incentivized to circumvent the backlog management process by approaching team members directly for assistance. Parties seeking assistance in matters that lie beyond the team’s remit can have an additional incentive, given that such activities would not be appropriate for inclusion on the team’s backlog in the first place. A good Servant Leader, such as a Scrum Master, will protect a team from such interference.

Too Busy: Key stakeholders often have responsibilities that span multiple teams (e.g. Product Owners, senior designers, and architects). If they do not value a team’s product or service particularly highly, they may be tempted to abdicate or defer their stakeholder duties in order to give other matters their attention. Sponsorship for the initiative is essential. Controlled Failure may be the best option in severe cases.

Unbounded Team: The allocation of team members to certain workstreams implies that they will not be available for others. This is a constraint on organizational behavior, since it means that managers cannot assign people to multiple duties in a reactive or ad-hoc manner. Organizations can be tempted to compromise on such discipline for the sake of expediency or in support of "firefighting". Teams should be able to inspect-and-adapt their own membership and to frame their own teamwork commitments.

Unbounded Timebox: Allow an indeterminate amount of time for the completion of a task. Teams can be tempted to try and extend an available time-box if, in so doing, it increases the chances of an intermediate goal being met. The team can then create the illusion of success even though the deliveries that were forecast have not been made. Good time-boxing will avoid this by ensuring that a maximum time limit is observed.

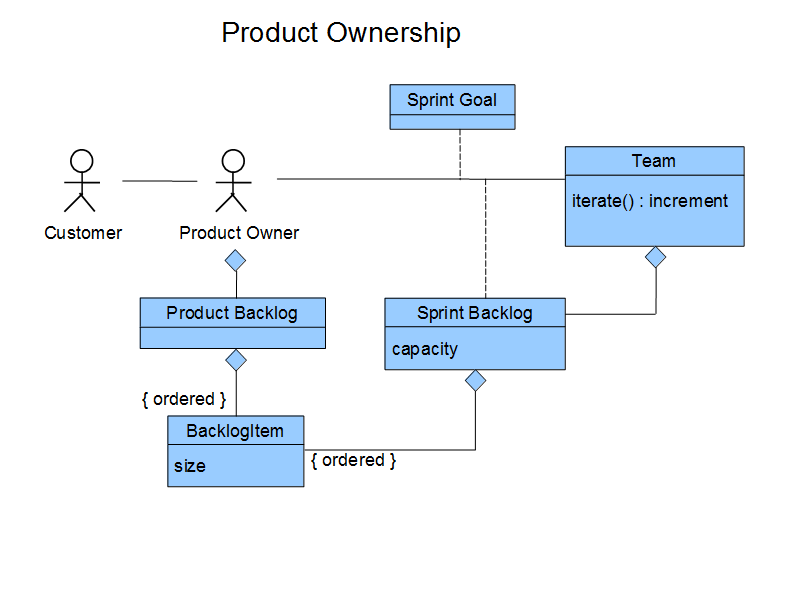

Uncommitment: Team members who do not value the Product or Sprint Goal, or who are allowed to accept other priorities, may be tempted to admit unplanned work into a Sprint. This can include work from forceful parties which the Product Owner does not value. Strong Product Ownership is important if this problem is to be overcome.

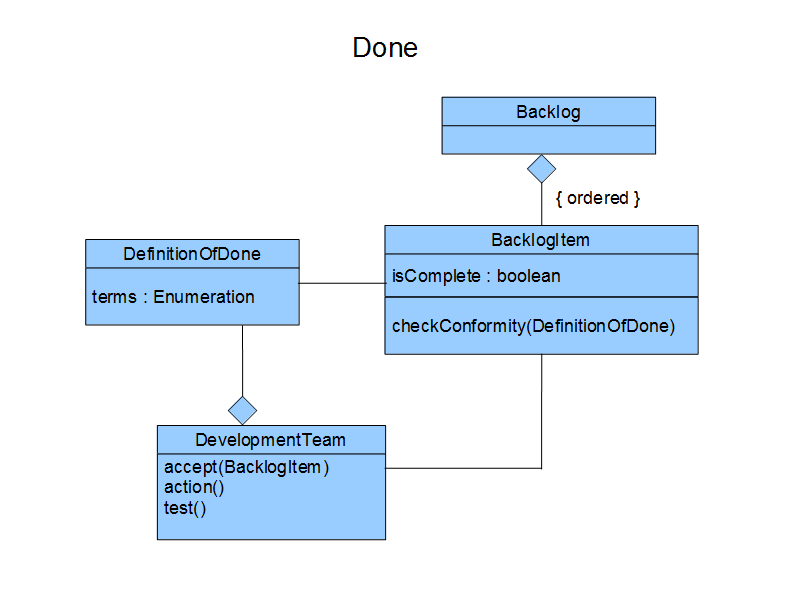

Undefined Done: Progress work as quickly as possible and without sufficient regard for quality. Technical debt is likely to result. Observing a Definition of Done which assures each increment as being of release quality is essential.

Unlimited WIP: When faced by competing and vociferous stakeholder demands, team members can feel obliged to action multiple items simultaneously. In an attempt to pacify stakeholders, they can therefore claim that an item is being worked on and is no longer enqueued. Both good Product Ownership and a team determination to limit WIP appropriately are needed to overcome this.

Unresolved Proxy: Multiple stakeholders can have an interest in a product and each may only be able to articulate the requirements in their area. Consequently a senior product owner may be tempted to delegate ownership to multiple proxies. Good product ownership ensures that one clear authority is accountable for value.

Vanity Metrics: Use only the most favorable metrics in order to strike a posture. Team members can be tempted to show their efforts in the best light rather than in a more objective one. Good metrics are based on data which supports inspection and adaptation and the taking of informed, constructive action.

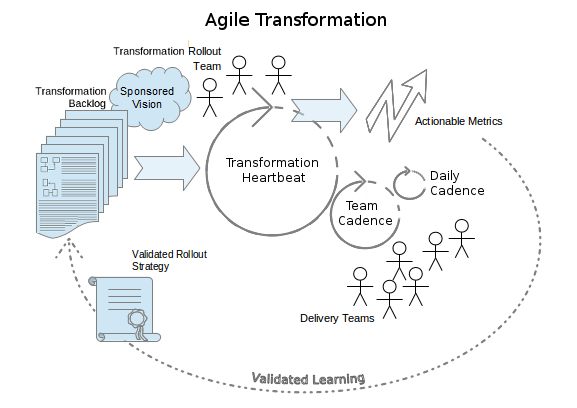

Waterscrumfall: Organizations may often have the goal of adopting an agile way of working, but they can lack the cultural grit to transition away from an established stage-gated culture. They then attempt to effect a compromise in which an iterative development approach is encapsulated within a development stage. In so doing they hope to leverage the benefits of agile practice, whilst not actually changing the organization's delivery approach or the terms of reference that are comfortable to stakeholders. The transformation pattern helps to challenge this thinking, as it puts empirical process control at the heart of an enterprise change attempt.

{{ parent.title || parent.header.title}}

{{ parent.tldr }}

{{ parent.linkDescription }}

{{ parent.urlSource.name }}